A case against the SHANTI Act, 2025

POLITY – BILL/ACT

13 FEBRUARY 2026

(Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Act, 2025

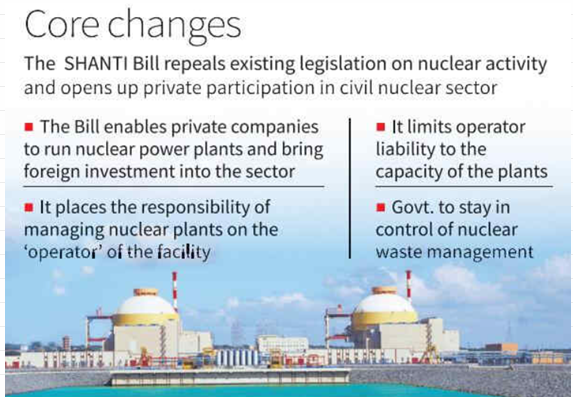

- The SHANTI Act, passed in the Winter Session of Parliament, makes major changes to India’s nuclear power framework by:

- Opening the sector to private operators

- Altering the liability regime

- Restructuring regulatory oversight

Critics argue that it weakens safety and accountability safeguards.

Key Features of the SHANTI Act

1. . Private Entry into Nuclear Power

- Ends the Union government’s exclusive control.

- Allows private entities to operate nuclear plants.

2. Changes to Liability Framework

Supplier Indemnity

- Liability for accidents is channelled solely to the operator.

- Removes the “right of recourse” (previously under CLNDA), which allowed operators to sue suppliers for defective equipment.

Liability Caps

- Operator liability:

- ₹100 crore (small plants)

- ₹3,000 crore (large plants)

- Total liability (including Centre):

- 300 million Special Drawing Rights (~₹3,900 crore)

Removal of Clause 46

- Victims can no longer invoke other laws (including criminal law) for additional remedies.

Critics say this protects suppliers and operators at the cost of victims.

3. Regulatory Structure

- Provides a legislative basis for the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB).

- However, Board members are selected by a committee constituted by the Atomic Energy Commission.

- Critics argue this limits regulatory independence.

Why Is Supplier Indemnity Controversial?

- Historically, major nuclear accidents involved design flaws:

- Fukushima (2011) – Weak containment structure.

- Chernobyl (1986) – Reactor design flaws and shutdown system failures.

- Three Mile Island (1979) – Control room design issues and communication failures.

- Critics argue that design defects have played central roles in past disasters, so shielding suppliers lacks scientific justification.

- However, U.S. suppliers had objected to India’s earlier liability regime.

- The 2026 U.S. National Defense Authorization Act urged India to align with international norms favouring suppliers.

Liability Cap vs Potential Damage

| Accident | Estimated Damage |

| Fukushima | ~₹46 lakh crore |

| Chernobyl (Belarus estimate) | ~₹21 lakh crore |

| SHANTI Act Cap | ~₹3,900 crore |

- The cap is roughly 1,000 times smaller than damage from major accidents.

- Even with international supplementary compensation, victims may receive less than 1% of potential losses.

Safety Concerns

- Moral Hazard

If operators and suppliers are shielded from full liability:

- They may take greater risks.

- Safety investments may decline.

- Natural Disaster Clause

- Operators indemnified for accidents caused by “grave natural disasters.”

- Critics say this weakens India’s earlier absolute liability principle for hazardous industries.

- Fukushima itself was triggered by a tsunami.

Nuclear Energy’s Role in India

- Contributes ~3% of electricity.

- Past targets repeatedly missed:

- 10 GW by 2000 → achieved 2.86 GW

- 20 GW by 2020 → achieved 6.78 GW

- New target: 100 GW by 2047.

Critics question feasibility due to:

- High capital costs

- Safety concerns

- Unproven small modular reactors

Economic Dimension

Nuclear projects involve massive commercial investments.

Example:

- Two AP1000 reactors in Georgia (U.S.) cost ~$18 billion each.

The Act:

- Creates opportunities for private and multinational firms.

- Shields them from extensive liability exposure.

Core Debate

| Supporters Say | Critics Say |

| Aligns with international norms | Weakens victim rights |

| Attracts private investment | Creates moral hazard |

| Speeds up nuclear expansion | Undermines accountability |

| Provides regulatory framework | Limits regulator independence |

Conclusion

- Should rapid nuclear expansion and commercial viability outweigh strict liability and victim protection in a high-risk industry?

- The answer depends on how India balances energy security, climate goals, safety and accountability and corporate risk-sharing.